Why a late dinner is bad news for your waistline

Is it bad to eat late at night? This question is coming up a lot in my work with clients. Luckily, several research groups are investigating how meal timing affects metabolic health. (And sleep – but I will talk about that latter point in more detail in a different post). In this blog, I will summarise the findings from two recent studies, and I focus on how the timing of your biggest daily meal and eating late can impact weight loss. And the opposite, weight gain and obesity.

A picture that has started to emerge suggests eating late is bad for your metabolic health. (‘Late’ doesn’t just mean ‘during the night’ as is the case for shift workers, but it also includes ‘dayworkers’ eating during the last few hours before bedtime.) I will explain the research in more detail below, but first I want to explain what metabolic health means.

What is metabolic health?

This is what I take metabolic health (without good/ poor/ healthy/ unhealthy in front of the term!) to mean: it’s an evaluation of how healthy your metabolism is. In other words, it’s a health status assessment of metabolic markers such as blood sugar, blood pressure, blood fats (including cholesterol) and waist circumference. And depending on the outcome levels, your metabolic health is somewhere along a spectrum of healthy to unhealthy.

Being metabolically healthy means that your body can absorb and process nutrients, and the risk of developing metabolic diseases (e.g. hypertension, diabetes, obesity) is low. Conversely, being metabolically unhealthy refers to state in which the body struggles to respond to nutrients in a healthy way. That is, it finds it difficult to regulate blood sugar, blood fats and other parameters following eating. Over time, this can lead to type-2 diabetes, weight gain, (systemic) inflammation, and other conditions affecting your physical and mental health.

Late eating vs early eating

Late eating has been linked to an increased obesity risk. But the underlying mechanism(s) was, until now, not very well understood. Two recent studies have ben able to shed some light on this though. And they report fascinating and, most importantly, complementary findings and interpretations of what might be going on.

Both studies compared the effects of two different eating conditions (eating early vs late) on markers linked to gaining weight. Within each study, the two conditions had exactly the same diet and calorie intake (isocaloric diet). It’s the timing participants consumed them that was different.

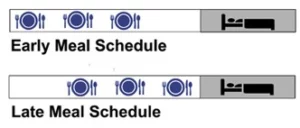

Vujović et al.1 investigated whether there’s a difference in hunger, energy expenditure, and fat tissue activity when participants ate all their meals earlier or later. The team found that late eating (the last meal started 2.5 hours before bedtime; see Figure 1) left people feeling hungrier and wanting to eat more (but weren’t allowed of course). It also lowered levels of leptin, the satiety hormone, which is probably why they felt hungrier. But there are two more interesting findings: When eating late, people spent less energy (burned less calories), and their fat tissue (adipose tissue) stored more fat.

Let’s now look at the second research piece. Ruddick-Collins2 and her colleagues had their participants eat most of their daily calories either in the morning or in the evening. While the three daily meals took place at the same time in each condition, what differed was the portion size (see Figure 2).

The researchers measured calories burned after each meal and found that there was no difference between the two eating conditions.* But here comes another very important finding: Eating your biggest meal in the morning left participants feeling less hungry for the rest of the day compared to eating your biggest meal in the evening.

Evidence stacks up

The message from the two studies is crystal clear: Eating late and/ or consuming most of your daily calories within your evening meal puts you on a sure path to obesity. It does so by altering your hunger and appetite levels, as well as prompting your body to store more fat. Unfortunately, obesity often leads to other illnesses and reduces the quality of your sleep. And inadequate sleep is yet another risk factor for poor cardio-metabolic health…enter a vicious circle of poor lifestyle choices-poor health-poor sleep.

Another mechanism for the observed association between eating late and obesity might be the body clock. Circadian rhythms can be found in almost all bodily processes and functions. Good examples are your hunger hormones and insulin. Insulin levels are lowest in the evening and at night, and the body is less able to regulate blood sugar levels following a (big) meal at this time. This not only increases the risk of obesity but also the risk of type 2 diabetes … And quickly we are back to the vicious circle I mentioned above.

What can you do?

My answer to clients asking about late eating therefore is simple: Eat early. If you want to maintain a healthy weight (or perhaps loose some) don’t get into the habit of eating late.

-Experiment with eating a bigger breakfast and a smaller dinner.

-Shift your eating window to start and finish earlier in the day. (I will write about the duration of the eating window in a separate blog soon.)

-And as always, don’t procrastinate bedtime and have a regular sleep window.

Do you have any questions on eating/ diet, and how these interact with sleep and the circadian clock? Send me an email or book an initial call with me.

Warmly,

Dr Kat

*This study ran for four weeks which is relatively short. It might be had it ran for longer that a difference in calories burned between the two eating conditions would have been observed.

References:

1 Vujović et al., 2022: Late isocaloric eating increases hunger, decreases energy expenditure, and modifies metabolic pathways in adults with overweight and obesity. Cell Metabolism 34, 1486–1498.

2Ruddick-Collins et al., 2022: Timing of daily calorie loading affects appetite and hunger responses without changes in energy metabolism in healthy subjects with obesity. Cell Metabolism 34, 1472–1485.